In the second of two articles looking at the potential impact of the Covid-19 crisis by looking at historical parallels and seeing what lessons can be learned from history, we look at the ways in which pandemics spread and what lessons can be drawn from historical pandemics.

The Spanish Flu of 1918-19 was the deadliest influenza pandemic in history and one of the most deadly pandemics ever. It infected an estimated 500 million people across the planet) which represented about 1/3 of the total population) and estimates of the death toll are between 17 million and 50 million.

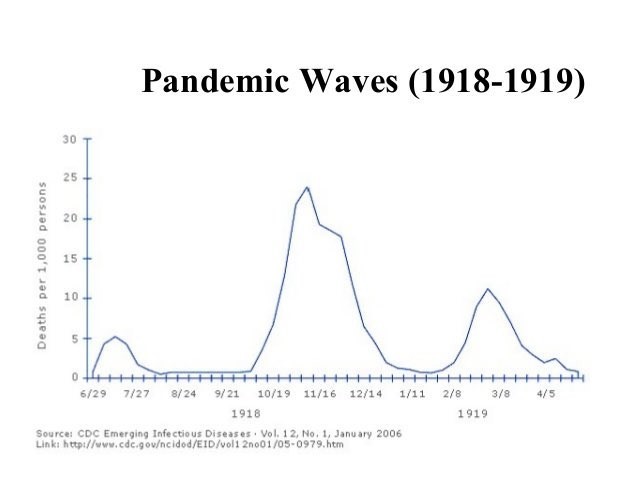

One of the characteristics of the Spanish Flu pandemic was its multiple waves (see below) and this is a feature of many flu-like pandemics – as can be seen in the 2009 influenza pandemic.

Spanish Flu first appeared in March 1918 and at the time, many people thought that it was very similar to a seasonal flu – whilst it did spread quickly through Europe, the mortality rate initially seemed similar to seasonal flu (around 0.1%). After an initial spike in the infections and fatalities in June and July 1918, the spread of the virus appeared to have slowed down and, by September 1918, everyone thought that this flu had simply run its course.

What happened next took everyone by surprise, with a huge surge in both infections and deaths which started in October and peaked in November 1918. The reasons for this are not fully understood, but the large troop movements around the world at the end of the First World War does seem to have played a major role in the disease spreading so quickly. The virus also seemed to mutate to a deadlier form and went from a disease with a fatality rate of around 0.1% to one between 2 and 10% – nearly one hundred times as fatal. It is worrying to note that the second wave killed many more people than the first wave did.

There is some debate around the exact mortality rate – partly because the science of epidemiology was still in its infancy and death certificate recording was fairly inconsistent. The public health response in 1918 was very similar to the public health response today, and in some countries people were told to socially isolate, told to stay indoors and there were widespread restrictions on public transport and businesses. In parts of the USA, people were fined for not wearing face masks and public gatherings were enforced by the police. There was also political disagreement regarding the trade-off between public health and the economic impact of social restrictions. It is reported that Dr. Arthur Newsholme (the chief medical officer for the Local Government Board, and the person primarily responsible for public health in England and Wales) allegedly knew that a strict civilian lockdown would save lives, but refused to order this as he was concerned about the impact on munitions factories and the war effort.

In the face of no curative solution, medical misinformation was in wide circulation and some doctors were advising patients to take 30 grams per day of Aspirin which a dose we now know to be fatal.

Despite strong government guidance and social action, a subsequent third wave of the Spanish Flu occurred – which killed even more people than the first wave. Current modelling has tried to decipher why the subsequent waves were more fatal and there is some evidence that this may have been because of acquired immunity. There is evidence that this may be because of behaviour change in the population at large. There is also some evidence that the mortality rate was much higher in urban areas and cities and that this was around 40% higher than in rural areas.

This is not simply a curiosity of the 1918-19 Spanish Flu and similar waves were also seen in the 2009 Flu Pandemic and the second wave there was also more deadly than the first wave.

So, what does this all mean in the context of the current Covid-19 Pandemic?

It certainly seems that there is a high likelihood of a second wave, and that the death rate is likely to be higher than that of the first wave. Many of the same public health measures are used today as were used in and 2009 – although arguably these are currently enforced much more vigorously. There has even been a brief second co-vid wave in Japan, with the second wave hitting 26 days after the first state of emergency was lifted. Professor Kenji Shibuya of King’s College London said of the second outbreak that “The key lesson is even if you are successful in containment locally but there is transmission going on in other parts of the country, as long as people are moving around, it’s difficult to maintain a virus-free status”.

The peak of the second wave in both 1918 and in 2009 were around 4 months later than the peak of the first wave and the second waves lasted around 3 months. If the same pattern happens in 2020 then a second peak would be expected in the UK in September 2020 and would last until November 2020. It is entirely possible that this could coincide with a seasonal flu outbreak which also happened in 1918 and 2009.

The main takeaway from this analysis is that we should not assume that the worst of the Covid-19 infections are behind us simply because we are beginning to see a tailing off of infections and fatalities. Both of the mentioned pandemics happened in the past, and both were followed by second waves which were more virulent and fatal. The social distancing and lockdown measures currently practiced will help, but these measures should not be seen as sufficient in and of themselves. We should at the very least prepare for a late autumn resurgence in infections and death and ensure that this is factored into our planning and our preparedness.